This is the second part of the talk I gave January 24, 2013 at the Ottawa Python Authors Group.

Part One introduces Python iterables and iterators and generators. This part covers the advanced use of generators while building an interactive two-player network game.

Generators in Depth

Generators’ ability to accept as well as produce data is useful for many purposes. The interface to generator objects is limited, unlike instances of classes we create, but generators enable a very powerful programming style.

Here is a “running average” calculator implemented as a generator. As shown in the previous section the generator state (total, count) is stored in local variables.

Notice the extra parenthesis around the first yield expression. This is required any time yield doesn’t appear immediately to the right of an assignment operator.

def running_avg():

"coroutine that accepts numbers and yields their running average"

total = float((yield))

count = 1

while True:

i = yield total / count

count += 1

total += i

This type of generator is driven by input to .send(). However, the code inside a generator must execute up to the first yield expression before it can accept any value from the caller. That means that the caller always has to call next() (or .send(None)) once after creating a generator object before sending it data.

If you try to send a value first instead, Python has a helpful error for you.

r = running_avg()

r.send(10)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-2-8c08c6a44ff3> in <module>()

1 r = running_avg()

----> 2 r.send(10)

TypeError: can't send non-None value to a just-started generator

So let’s call next() to advance the program counter to the first yield expression, then start passing values we would like averaged.

next(r)

r.send(10)

10.0

r.send(5)

7.5

r.send(0)

5.0

r.send(0)

3.75

A convenient decorator

The flow is always the same when working with generators.

- a generator object is created by the caller

- the caller starts the generator

- the generator passes data to the caller (or signals the end of the sequence)

- the caller passes data to the generator

- repeat from (3)

For generators that are driven by input to .send() no data is transferred in the first 3 steps above.

This is a decorator that arranges for next() to be called once immediately after a generator is created. This will turn a generator function into a function that returns a generator immediately ready to receive data (step 4).

def advance_generator_once(original_fn):

"decorator to advance a generator once immediately after it is created"

def actual_call(*args, **kwargs):

gen = original_fn(*args, **kwargs)

assert next(gen) is None

return gen

return actual_call

We apply our decorator to running_avg().

running_avg = advance_generator_once(running_avg)

And now we don’t need to call next() every time we create a new running average generator.

r = running_avg()

r.send(42)

42.0

Coroutine development is protocol development

As shown, one of the ways to pass a message to a generator is with .send(). This interface allows you to pass a single object to a generator. For this object we can pass tuples, dicts or anything else we choose.

You decide the protocol for your generator by documenting the types and values of objects you will send from caller to generator and yield from generator to caller.

Tuples are perfect for a generator that needs two objects each time, e.g. a player number and a key press.

This is a Rock-Paper-Scissors game where each player’s play is passed in separately, and once both players have played the result of the game is yielded. Players can change their mind choose a different play if the other player hasn’t chosen yet. Games will continue indefinitately.

This generator uses a common pattern of storing the result that will be yielded in a local variable so that there are fewer yield statements in the generator function. Having fewer yield statements makes it easier to understand where it is possible for execution to be paused within the generator function.

The outer while loop runs once for each full game. The inner while loop collects input from the users until the game result can be decided.

@advance_generator_once

def rock_paper_scissors():

"""

coroutine for playing rock-paper-scissors

yields: 'invalid key': invalid input was sent

('win', player, choice0, choice1): when a player wins

('tie', None, choice0, choice1): when there is a tie

None: when waiting for more input

accepts to .send(): (player, key):

player is 0 or 1, key is a character in 'rps'

"""

valid = 'rps'

wins = 'rs', 'sp', 'pr'

result = None

while True:

chosen = [None, None]

while None in chosen:

player, play = yield result

result = None

if play in valid:

chosen[player] = play

else:

result = 'invalid key'

if chosen[0] + chosen[1] in wins:

result = ('win', 0) + tuple(chosen)

elif chosen[1] + chosen[0] in wins:

result = ('win', 1) + tuple(chosen)

else:

result = ('tie', None) + tuple(chosen)

We play this game by passing (player number, play) tuples to .send()

rps = rock_paper_scissors()

rps.send((0, 'r'))

rps.send((1, 'p'))

('win', 1, 'r', 'p')

rps.send((1, 's'))

rps.send((1, 'p'))

rps.send((1, 'z'))

'invalid key'

rps.send((0, 's'))

('win', 0, 's', 'p')

rps.send((0, 'r'))

rps.send((1, 'r'))

('tie', None, 'r', 'r')

Make the caller wait

It makes sense to design your generator protocols so that any waiting has to be done by the caller. This includes waiting for user input, IO completion and timers. The rock, paper scissors example above and all the examples to follow are designed this way.

The benefit of waiting in the caller is that other processing (and other generators) can be “running” at the same time without needing multiple processes or threads.

Generators with try: finally:

try: finally: blocks in normal Python code are great for managing an external resources. try: finally: blocks work just fine in generators too, you can use them to ensure a resource aquired inside a generator is properly cleaned up no matter how the generator is used. The generator could run to completion, raise an exception or simply be garbage collected after the last reference to it is removed and the finally: block will always be executed.

This generator sets the terminal attached to fd into “cbreak” mode when it is created and then restores the original terminal setting on exit. cbreak mode allows reading each key the user types as they are typed, instead of waiting for a full line of text.

Note that the first yield statement is inside the try: block, guaranteeing that the finally: block will be executed eventually. The first yield statement yields None (which is what is expected by the advance_generator_once decorator). The advance_generator_once decorator makes sure next() is immediately called on this generator after creation, so the terminal is always set to cbreak mode after the caller calls cbreak_keys().

The finally: block in this generator is useful in normal operation and for debugging. When the program exits the terminal will be restored to normal mode. If the terminal is left in cbreak mode tracebacks shown will be sprayed across the screen in a hard-to-read manner, and the user’s shell prompt won’t echo input normally.

import os

import termios

import tty

@advance_generator_once

def cbreak_keys(fd):

"enter cbreak mode and yield keys as they arrive"

termios_settings = termios.tcgetattr(fd)

tty.setcbreak(fd)

try:

yield # initialize step

while True:

yield os.read(fd, 1)

finally:

termios.tcsetattr(fd, termios.TCSADRAIN, termios_settings)

Testing this generator involves creating a “psuedo-tty” for the generator to connect to, then simulating user input on that pseudo-tty. In this test we read just 5 characters because reading any more would block.

import pty

import itertools

master, slave = pty.openpty()

old_settings = termios.tcgetattr(master)

os.write(slave, "hello")

c = cbreak_keys(master)

for i in range(5):

print(next(c), end=' ')

h e l l o

We still hold a reference to the generator, so our pseudo-tty is still in cbreak mode.

old_settings == termios.tcgetattr(master)

False

We could remove the reference, or we can be more explicit by calling the generator’s .close() method. The .close() method causes a GeneratorExit exception to be raised within the generator.

When the caller uses the .close() method it expects the generator to exit. If the generator yields a value instead, .close() raises a RuntimeError. Generators must exit normally or raise an exception when a GeneratorExit is raised.

c.close()

old_settings == termios.tcgetattr(master)

True

Sockets are another type of external resource that needs to be properly managed.

When using sockets it’s polite to shut down the socket so the other side knows you’re done sending. It’s also a very good idea to close the socket to free up the file descriptor allocated by the operating system.

This generator reads individual characters from a socket and on exit politely tries to shutdown the socket, and next ensures that the socket is closed.

import socket

@advance_generator_once

def socket_read_and_close(sock):

"yields strings from sock and ensures sock.shutdown() is called"

try:

b = None

while b != '':

yield b

b = sock.recv(1)

finally:

try:

sock.shutdown(socket.SHUT_RDWR)

except socket.error:

pass

sock.close()

Testing socket code takes quite a few lines of boilerplate. We have to find a free port, set up a server socket and then accept a client connection as another socket object.

We send some text and immediately disconnect the “client” to verify that our generator exits cleanly after reading all the data on the “server” side.

import socket

server = socket.socket()

server.bind(('', 0))

server.listen(0)

host, port = server.getsockname()

client = socket.socket()

client.connect(('localhost', port))

s, remote = server.accept()

client.send("world")

client.shutdown(socket.SHUT_RDWR)

for c in socket_read_and_close(s):

print(c, end=' ')

w o r l d

The socket object has been closed, so if we try to wrap another generator around it we expect to get an error.

next(socket_read_and_close(s))

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

error Traceback (most recent call last)

/home/ian/git/iterables-iterators-generators/<ipython-input-64-012fa39a25b8> in <module>()

----> 1 next(socket_read_and_close(s))

/home/ian/git/iterables-iterators-generators/<ipython-input-62-8840110348a1> in socket_read_and_close(sock)

9 while b != '':

10 yield b

---> 11 b = sock.recv(1)

12 finally:

13 try:

/usr/lib/python2.7/socket.pyc in _dummy(*args)

168 __slots__ = []

169 def _dummy(*args):

--> 170 raise error(EBADF, 'Bad file descriptor')

171 # All _delegate_methods must also be initialized here.

172 send = recv = recv_into = sendto = recvfrom = recvfrom_into = _dummy

error: [Errno 9] Bad file descriptor

State machine generators

Generators are great for representing state machines.

Telnet is a protocol for allowing untrusted, insecure connections from remote hosts. It’s one option for plain terminal connections, and almost every operating system comes with a client.

For reading user input however, telnet has a bunch of control sequences that we need to filter out. Fortunately filtering out the control sequences with a little state machine is easy.

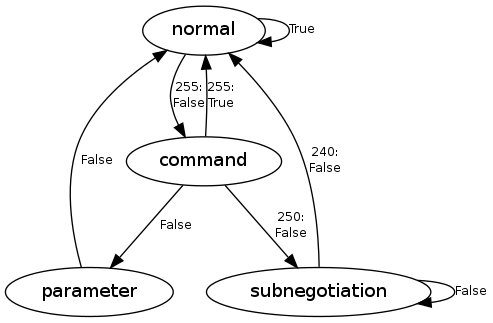

Starting in telnet normal mode all bytes except 255 are user input. A 255 byte enters command mode, which is followed by either one command byte and one parameter byte, or a 250 command byte and any number of subnegotiation bytes ending with a 240. On the transitions we mark True for user data and False for part of a control sequence.

The generator that implements this state machine isn’t much longer than the diagram that describes it. The states “normal”, “command”, “parameter” and “subnegotiation” are represented as yield statements. The transitions are normal python flow statements while: if: and continue.

The pattern of storing the result in a local variable actual_input is used here for the “normal” state because some transitions to the normal state yield True and others yield False.

@advance_generator_once

def telnet_filter():

"""

coroutine accepting characters and yielding True when the character

passed is actual input or False when it is part of a telnet command.

"""

actual_input = None

while True:

key = yield actual_input # normal

if key != chr(255):

actual_input = True

continue

key = yield False # command

if key == chr(255):

actual_input = True

continue

actual_input = False

if key == chr(250):

while key != chr(240):

key = yield False # subnegotiation

else:

yield False # parameter

This generator yields True and False values for each byte sent to it. To test it we print the characters sent where the generator yielded True. This is a capture of a control sequences sent from a modern telnet client with the 6 characters “signal” mixed between the control sequences.

keep = telnet_filter()

chatter = ('\xff\xfd\x03si\xff\xfb"gn\xff\xfa"\x03\x01\x00\x00\x03b'

'\x03\x04\x02\x0f\x05\x00\x00\x07b\x1c\x08\x02\x04\tB\x1a'

'\n\x02\x7f\x0b\x02\x15\x0f\x02\x11\x10\x02\x13\x11\x02'

'\xff\xff\x12\x02\xff\xff\xff\xf0al\xff\xfd\x01')

for c in chatter:

if keep.send(c):

print(c, end=' ')

s i g n a l

Combining generators

It’s easy to combine simple generators for more advanced functionality. We can combine our socket_read_and_close() generator with some new telnet negotiation and our telnet_filter() generator to make a new “clean” character-by-character telnet input generator. This generator will yield only the user input from a telnet connection.

Be careful of when combining generators, though. If a “child” generator raises a StopIteration exception when you call its next() method that exception will propagate normally in the “parent” generator, causing it to exit as well. This can lead to some hard to find bugs, so always think about what you want to happen when your child raises StopIteration. If you want to handle StopIteration you can catch it like any other exception, or you can use the default parameter of the next() builtin function when advancing the child generator.

In this case we do want the new telnet_keys() parent generator to stop when the socket_read_and_close() child generator does, so we let its StopIteration exception carry through.

@advance_generator_once

def telnet_keys(sock):

"yields next key or None if key was a filtered out telnet command"

# negotiate character-by-character, disable echo

sock.send('\xff\xfd\x22\xff\xfb\x01')

keep = telnet_filter()

s = socket_read_and_close(sock)

yield

while True:

# allow StopIteration to carry through:

c = next(s)

if keep.send(c):

yield c

else:

yield None

High-level decision making with generators

Rock, paper, scissors isn’t much fun when played single player in the Python read-eval-print-loop.

We should be able to play it with single keystrokes on the console. Opponents (guests) should be able to connect to play against us. Once they connect we should play a few games before we choose a winner. We need to handle a guest disconnecting before all the games have been played. Also, if the guest waits too long to make a move they should be disconnected so someone else can play. Finally, we should have reporting of how well we’ve done against all the guests that have connected.

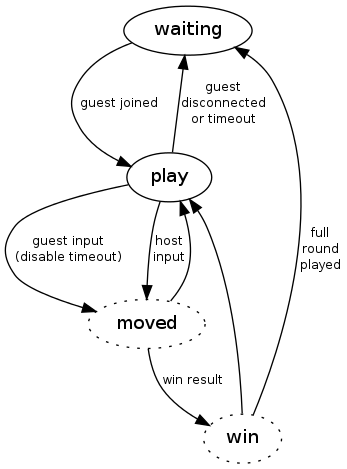

For the game itself we can lay out the states and transitions. There are only really two states: “waiting” for a guest to connect and “play” while we’re playing. “Moved” and “win” below are just steps in deciding whether we end up in the “play” or “waiting” state.

There are many transitions with different effects. When guest enters a play we should disable the timeout that will disconnect them. When a player has moved, play may continue because one player still needs to move or because the game was a tie. When a game ends with one player winning play will continue until a full round has been played when the guest will be disconnected.

This generator is responsible for providing prompts and feedback to both players, including game results. It accepts and processes input from both players and notifies players when their input is invalid. It also asks the caller to disconnect the opponent once enough games have been played by yielding 'waiting'. Finally this generator manages control of the opponent timeout by yielding 'reset timeout' when the timer should be (re)started and 'disable timeout' when the opponent has entered a valid play.

The caller is responsible for receiving input from the users, sending output to the users and informing the generator when the opponent connects, disconnects or has timed out. The disconnect and timeout conditions are somewhat exceptional so they have been implemented with the use of the generator’s .throw() method.

Exceptions passed to a generator’s .throw() method are raised within the generator from the current yield statement, just like how the .close() method raises GeneratorExit. Exceptions may then be handled by the generator with try: except: blocks. Here we handle the exceptions by printing a message and returning to the outer while: loop (the “waiting” state).

class Timeout(Exception):

pass

class Disconnect(Exception):

pass

def game_machine(game_factory, output, best_of=9):

"""

coroutine that manages and provides comminication for two-player games,

best of N

:param game_factory: a function that returns a game generator object

:param output: a function that sends output to one or both players

:param best_of: max games to play per guest (an odd number)

yields: 'waiting' : waiting for a guest (disconnect any existing guest)

'play': playing a game, accepting input

'disable timeout': disable the guest timout, accepting input

'reset timeout': reset and start guest timeout, accepting input

accepts to .send():

('join', guest_name): Guest guest_name joined

('key', (player_num, key)): Input from player player_num (0 or 1)

accepts to .throw(): Disconnect: the guest disconnected

Timeout: the guest timout fired

"""

ravg = running_avg()

while True:

event, value = yield 'waiting'

if event != 'join':

continue

game = game_factory()

wins = [0, 0]

output("Player connected: {0}".format(value), player=0)

output("Welcome to the game", player=1)

try:

response = 'reset timeout'

while True:

event, value = yield response

response = 'play'

if event != 'key':

continue

player, key = value

result = game.send((player, key))

if result == 'invalid key':

output("Invalid key", player=player)

continue

elif player == 1:

response = 'disable timeout'

if not result:

continue

outcome, player, play0, play1 = result

output("Player 0: {0}, Player 1: {1}".format(play0, play1))

if outcome == 'win':

wins[player] += 1

output("Player {0} wins!".format(player))

output("Wins: {0} - {1}".format(*wins))

output("Overall: {0:5.2f}%".format(

(1 - ravg.send(player)) * 100), player=0)

if any(count > best_of / 2 for count in wins):

output("Thank you for playing!")

break

response = 'reset timeout'

except Disconnect:

output("Opponent disconnected.", player=0)

except Timeout:

output("Timed out. Good-bye")

To test this generator we need a simple output function with a default value for the player parameter.

def say(t, player='all'):

print(player, ">", t)

g = game_machine(rock_paper_scissors, say)

next(g)

'waiting'

g.send(('join', 'Ernie'))

0 > Player connected: Ernie

1 > Welcome to the game

'reset timeout'

g.send(('key', (0, 'r')))

'play'

g.send(('key', (1, 's')))

all > Player 0: r, Player 1: s

all > Player 0 wins!

all > Wins: 1 - 0

0 > Overall: 100.00%

'reset timeout'

g.throw(Disconnect())

0 > Opponent disconnected.

'waiting'

g.send(('join', 'Bert'))

0 > Player connected: Bert

1 > Welcome to the game

'reset timeout'

g.send(('key', (1, 'x')))

1 > Invalid key

'play'

g.send(('key', (1, 'p')))

'disable timeout'

g.send(('key', (0, 'r')))

all > Player 0: r, Player 1: p

all > Player 1 wins!

all > Wins: 0 - 1

0 > Overall: 50.00%

'reset timeout'

for player, key in [(0, 's'), (1, 'p')] * 5:

r = g.send(('key', (player, key)))

r

all > Player 0: s, Player 1: p

all > Player 0 wins!

all > Wins: 1 - 1

0 > Overall: 66.67%

all > Player 0: s, Player 1: p

all > Player 0 wins!

all > Wins: 2 - 1

0 > Overall: 75.00%

all > Player 0: s, Player 1: p

all > Player 0 wins!

all > Wins: 3 - 1

0 > Overall: 80.00%

all > Player 0: s, Player 1: p

all > Player 0 wins!

all > Wins: 4 - 1

0 > Overall: 83.33%

all > Player 0: s, Player 1: p

all > Player 0 wins!

all > Wins: 5 - 1

0 > Overall: 85.71%

all > Thank you for playing!

'waiting'

Driving an event loop with a generator

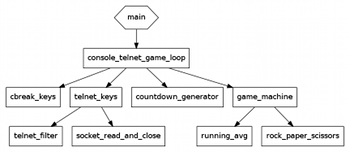

Now we need to pull all the peices together in a way that a select.select() loop can run the whole thing.

This generator accepts input on the console for player 0 with cbreak_keys(), and listens on a TCP port for player 1 (the guest) to connect. When player 1 connects it accepts input on that socket as a telnet connection with telnet_keys(). Input from both players is forwarded to game_machine(). When game_machine() asks for the timer to be reset this generator creates a countdown_generator() that will be used to give player 1 a countdown as their time is running out.

The caller is expected to be running select.select() in a loop. select.select() expects a list of file descriptors that might have data waiting and optionally a timeout value. The file descriptors passed will either be the console and server socket when player 1 is not connected, or the console and the client socket when player 1 is connected. The timeout will be set if there is a countdown in progress. select.select() yields a list of the file descriptors that are readable, or an empty list if the timeout was reached.

import socket

import sys

import time

def console_telnet_game_loop(game_factory, countdown_factory, best_of=9,

stdin=None, port=12333, now=None):

"""

Coroutine that manages IO from console and incoming telnet connections

(one client at a time), and tracks a timeout for the telnet clients.

Console and telnet client act as player 0 and 1 of a game_machine.

:param game_factory: passed to game_machine()

:param coutdown_factory: function returning a countdown generator

:param best_of: passed to game_machine()

:param stdin: file object to use for player 0, default: sys.stdin

:param port: telnet port to listen on for player 1

:param now: function to use to get the current time in seconds,

default: time.time

yields args for select.select(*args)

accepts to .send() the fd lists returned from select.select()

"""

if stdin is None:

stdin = sys.stdin

if now is None:

now = time.time

server = socket.socket()

server.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

server.bind(('', port))

server.listen(0)

print("Listening for telnet connections on port", port)

client = None

client_reader = None

timeout = None

countdown = None

local_fd = stdin.fileno()

local_user = cbreak_keys(local_fd)

def output(txt, player='all'):

if player != 1:

print(txt)

if player != 0 and client:

client.send(txt + '\r\n')

g = game_machine(game_factory, output, best_of)

state = next(g)

while True:

if state == 'waiting' and client:

client = client_reader = timeout = None

if state == 'reset timeout':

countdown = countdown_factory(lambda n: output(str(n), player=1))

timeout = time.time() + next(countdown)

state = 'play'

if state == 'disable timeout':

countdown = timeout = None

telnet_fd = client.fileno() if client else server.fileno()

timeout_seconds = max(0, timeout - now()) if timeout else None

readable, _, _ = yield [local_fd, telnet_fd], [], [], timeout_seconds

if not readable: # no files to read == timeout, advance countdown

try:

timeout = now() + next(countdown)

except StopIteration:

state = g.throw(Timeout())

timeout = None

continue

if local_fd in readable: # local user input

state = g.send(('key', (0, next(local_user))))

readable.remove(local_fd)

continue

if client: # client input

try:

key = next(client_reader)

except StopIteration:

state = g.throw(Disconnect())

else:

if key: # might be None if telnet commands were filtered

state = g.send(('key', (1, key)))

continue

# accept a new client connection

client, addr = server.accept()

client_reader = telnet_keys(client)

next(client_reader)

state = g.send(('join', str(addr)))

The big picture

The last peice we need is a main() funtion to drive our generators. All the waiting for IO and timers is done here, controlled from the generators above.

This design lets us easily switch to different event loop or async library. We could also run many of these games or many different tasks on the same event loop.

import select

def main():

loop = console_telnet_game_loop(rock_paper_scissors, countdown_generator)

fd_lists = None

while True:

select_args = loop.send(fd_lists)

fd_lists = select.select(*select_args)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

We end up with about 300 lines of code, including docstrings and more than 90% of that code is generators.

You may download it from https://raw.github.com/wardi/iterables-iterators-generators/master/rps_server.py

This code is a complete interactive game server. It supports character-by-character input with one player on the console and one connected by telnet. It detects players disconnecting and has a timer and countdown for disconnecting idle players. It also collects and reports game statistics.

This code contains no classes other than the simple Timeout and Disconnect exceptions. Message passing is accomplished with tuples, strings and integers.

All of the code is easy to test. The limited nature of the generator interface encourages us to break up code into small, simple, testable parts.

This code is 100% asynchronous with no threads, callback chains, queues, locking or monkey patching required.

Summary

Iterables

- may create an iterator with

iter(x)- implement

.__getitem__(), which raisesIndexErrorafter the last element - or implement

.__iter__()

- implement

Iterators

- are iterables, where

iter(x)typically returnsx - maintain some kind of “position” state

- implement

.__next__(), which raisesStopIterationafter the last element

Generators

- are iterators

- come with

.next(),.send(value),.close()and.throw(exception)methods for free! - “position” state includes local variables and program counter

- PEP 380: delegation with “yield from” available in Python 3.3+

- CAUTION:

StopIterationexceptions will cause trouble: consider next(x, default) builtin

See also

- Python’s built-in itertools module inspired by constructs from APL, Haskell, and SML

- Ned Bachelder’s Python Iteration Talk http://bit.ly/pyiter

- David M. Beazley’s Generator Tricks for Systems Programmers http://www.dabeaz.com/generators/

- David M. Beazley’s Curious Course on Coroutines and Concurrency http://dabeaz.com/coroutines/

- The future: PEP 3156: Unified Asynchronous IO Support (Twisted, Tornado, ZeroMQ)